Bruno Taut, Glass Pavillion, Cologne, destroyed, Expressionist Architecture

Erich Mendelsohn, Einstein Tower, Potsdam, Expressionist Architecture

Walter Gropius, The Fagus Shoe Factory

Lionel Feininger, Cathedral, woodcut from the Bauhaus Manifesto

The Bauhaus Basic Course, Josef Albers with students, 1928

Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, Photogram, Bauhaus

Herbert Bayer, design for a news kiosk, Bauhaus

Marcel Breuer, Wassily Chair, Bauhaus

Marianne Brandt, tea set, Bauhaus

Wilhelm Wagenfeld, Electric Table Lamp, Bauhaus

Gunta Stözl, Wall Hanging, Bauhaus

Faculty Apartment for Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, Bauhaus campus, Dessau, photographed in 1927

Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus faculty, Bauhaus Campus, Dessau, Bauhaus

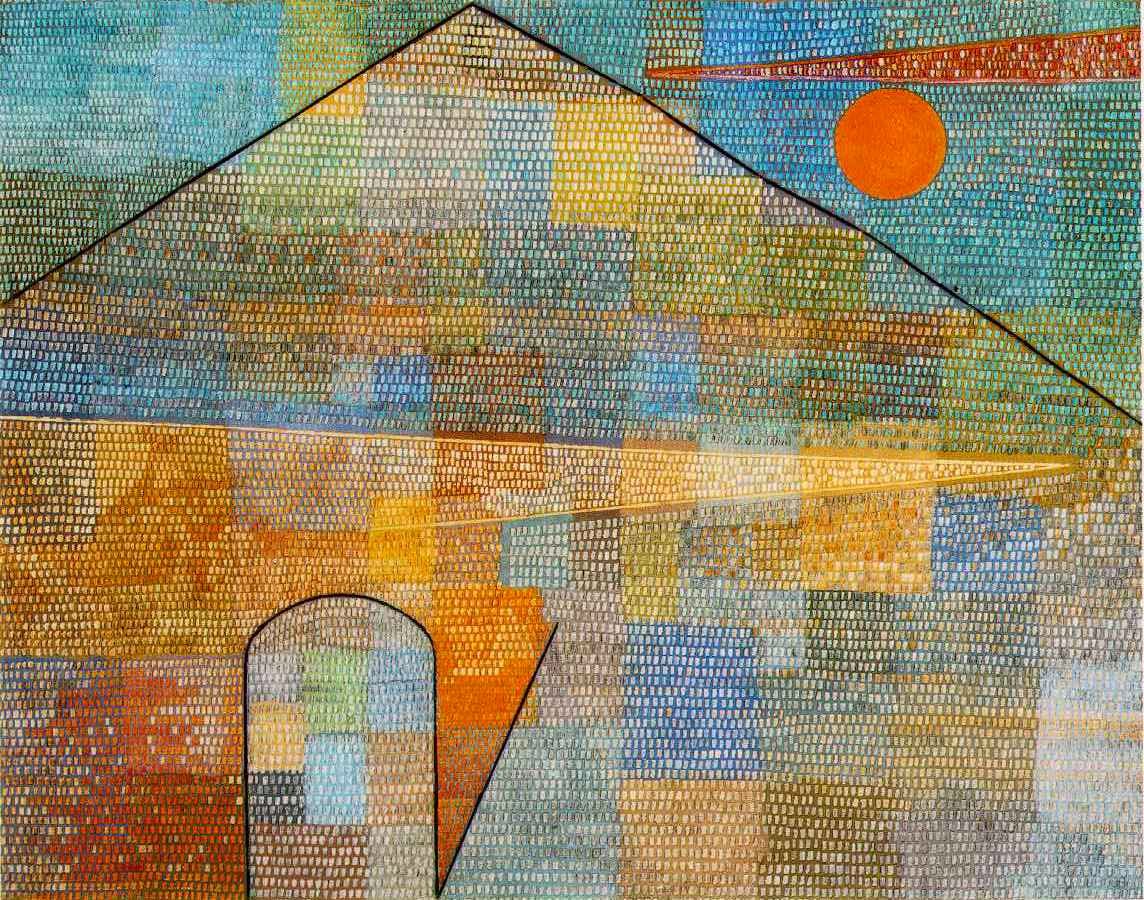

Paul Klee, Ad Parnassum, Bauhaus

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, proposed glass office building for the Friedrichstrasse, Berlin, International Modernism.

Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe, German Pavillion at the 1929 Barcelona Exhibition

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye, International Modernism

Le Corbusier, Unite d'Habitation, Marseilles, International Modernism

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater, Bear Run, PA

ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN BETWEEN THE WARS

Expressionist Architecture

--glass

--Bruno Taut

--Erich Mendelsohn

The Bauhaus

--Walter Gropius

--Johannes Itten

--Lazlo Moholy-Nagy

--Bauhaus Basic Course

International Modernism

--Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe

--Le Corbusier

-----The Radiant City

Frank Lloyd Wright

The Original Futurama

Before it became the namesake of a show on Comedy Central, the Futurama was an enormous series of dioramas in the General Motors pavilion at the 1939 - 1940 World's Fair in New York City (Corona Park in Queens). Designed by Norman Bel Geddes, this huge diorama series was built to be a glimpse 20 years into the future as imagined by General Motors. This was the most popular exhibit at the fair. Visitors stood in line for hours to ride the moving chairs with the speakers telling them all about the wonders of things to come in 1960.

The General Motors Pavilion at the 1939-1940 New York World's Fair; note the long lines waiting to get in.

People riding the mobile chairs looking at the dioramas designed by Norman Bel Geddes

Part of Norman Bel Geddes' diorama showing a huge highway intersection flanked by 4 quarter of a mile high skyscrapers in the future, in 1960.

Here is a film about the Futurama produced by General Motors in 1940, To New Horizons. It starts out in black and white, but the Futurama itself is all filmed in Technicolor.

The USA was still going through the Great Depression during the 1939 - 1940 Fair. This vision of a brighter, more spacious, and more hopeful future filled with opportunity thrilled audiences living in the bleak and cramped world of the 1930s. This is the future as imagined by a major car manufacturer with lots of emphasis on roads and transportation. After World War II, the United States and almost all of its major cities would be completely rebuilt to accommodate the automobile. Some of Bel Geddes' design is still praised for being so far-sighted, especially in his extensive use of continuous park space in cities and along river fronts. Other aspects might have been just a little too sweeping. There's no room in any of it for historical preservation or for mass transit.